Termination and splicing

ST connectors on multi-mode fiber.

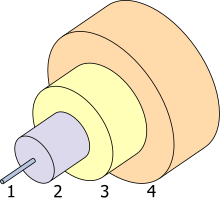

Optical fibers are connected to terminal equipment by optical fiber connectors. These connectors are usually of a standard type such as FC, SC, ST, LC, MTRJ, or SMA, which is designated for higher power transmission.

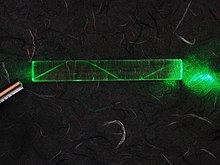

Optical fibers may be connected to each other by connectors or by splicing, that is, joining two fibers together to form a continuous optical waveguide. The generally accepted splicing method is arc fusion splicing, which melts the fiber ends together with an electric arc. For quicker fastening jobs, a “mechanical splice” is used.

Fusion splicing is done with a specialized instrument that typically

operates as follows: The two cable ends are fastened inside a splice

enclosure that will protect the splices, and the fiber ends are stripped

of their protective polymer coating (as well as the more sturdy outer

jacket, if present). The ends are cleaved (cut) with a precision

cleaver to make them perpendicular, and are placed into special holders

in the splicer. The splice is usually inspected via a magnified viewing

screen to check the cleaves before and after the splice. The splicer

uses small motors to align the end faces together, and emits a small

spark between electrodes at the gap to burn off dust and moisture. Then the splicer generates a larger spark that raises the temperature above the melting point

of the glass, fusing the ends together permanently. The location and

energy of the spark is carefully controlled so that the molten core and

cladding do not mix, and this minimizes optical loss. A splice loss

estimate is measured by the splicer, by directing light through the

cladding on one side and measuring the light leaking from the cladding

on the other side. A splice loss under 0.1 dB is typical. The complexity

of this process makes fiber splicing much more difficult than splicing

copper wire.

Mechanical fiber splices are designed to be quicker and easier to

install, but there is still the need for stripping, careful cleaning and

precision cleaving. The fiber ends are aligned and held together by a

precision-made sleeve, often using a clear index-matching gel

that enhances the transmission of light across the joint. Such joints

typically have higher optical loss and are less robust than fusion

splices, especially if the gel is used. All splicing techniques involve

installing an enclosure that protects the splice.

Fibers are terminated in connectors that hold the fiber end precisely

and securely. A fiber-optic connector is basically a rigid cylindrical

barrel surrounded by a sleeve that holds the barrel in its mating

socket. The mating mechanism can be push and click, turn and latch (bayonet mount), or screw-in (threaded).

A typical connector is installed by preparing the fiber end and

inserting it into the rear of the connector body. Quick-set adhesive is

usually used to hold the fiber securely, and a strain relief

is secured to the rear. Once the adhesive sets, the fiber's end is

polished to a mirror finish. Various polish profiles are used, depending

on the type of fiber and the application. For single-mode fiber, fiber

ends are typically polished with a slight curvature that makes the mated

connectors touch only at their cores. This is called a physical contact (PC) polish. The curved surface may be polished at an angle, to make an angled physical contact (APC)

connection. Such connections have higher loss than PC connections, but

greatly reduced back reflection, because light that reflects from the

angled surface leaks out of the fiber core. The resulting signal

strength loss is called gap loss. APC fiber ends have low back reflection even when disconnected.

In the 1990s, terminating fiber optic cables was labor-intensive. The

number of parts per connector, polishing of the fibers, and the need to

oven-bake the epoxy in each connector made terminating fiber optic

cables difficult. Today, many connectors types are on the market that

offer easier, less labor-intensive ways of terminating cables. Some of

the most popular connectors are pre-polished at the factory, and include

a gel inside the connector. Those two steps help save money on labor,

especially on large projects. A cleave

is made at a required length, to get as close to the polished piece

already inside the connector. The gel surrounds the point where the two

pieces meet inside the connector for very little light loss.[citation needed]

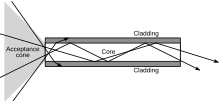

Free-space coupling

It is often necessary to align an optical fiber with another optical fiber, or with an optoelectronic device such as a light-emitting diode, a laser diode, or a modulator. This can involve either carefully aligning the fiber and placing it in contact with the device, or can use a lens

to allow coupling over an air gap. In some cases the end of the fiber

is polished into a curved form that makes it act as a lens. Some

companies can even shape the fiber into lenses by cutting them with

lasers.[65]

In a laboratory environment, a bare fiber end is coupled using a fiber launch system, which uses a microscope objective lens to focus the light down to a fine point. A precision translation stage

(micro-positioning table) is used to move the lens, fiber, or device to

allow the coupling efficiency to be optimized. Fibers with a connector

on the end make this process much simpler: the connector is simply

plugged into a pre-aligned fiberoptic collimator, which contains a lens

that is either accurately positioned with respect to the fiber, or is

adjustable. To achieve the best injection efficiency into single-mode

fiber, the direction, position, size and divergence of the beam must all

be optimized. With good beams, 70 to 90% coupling efficiency can be

achieved.

With properly polished single-mode fibers, the emitted beam has an

almost perfect Gaussian shape—even in the far field—if a good lens is

used. The lens needs to be large enough to support the full numerical

aperture of the fiber, and must not introduce aberrations in the beam. Aspheric lenses are typically used.

Fiber fuse

At high optical intensities, above 2 megawatts per square centimeter, when a fiber is subjected to a shock or is otherwise suddenly damaged, a fiber fuse

can occur. The reflection from the damage vaporizes the fiber

immediately before the break, and this new defect remains reflective so

that the damage propagates back toward the transmitter at 1–3 meters per

second (4–11 km/h, 2–8 mph).[66][67] The open fiber control system, which ensures laser eye safety in the event of a broken fiber, can also effectively halt propagation of the fiber fuse.[68]

In situations, such as undersea cables, where high power levels might

be used without the need for open fiber control, a "fiber fuse"

protection device at the transmitter can break the circuit to keep

damage to a minimum.